Guest Preacher Dana Cassell

Mark 4:26-34

During the pandemic, I got really into gardening. I started volunteering at my local food pantry and community garden, the Parktown Food Hub, and then got hired to be what they called the “Garden Minister.” I was super excited to find a new community garden just a few minutes’ walk from my house when I moved to Roanoke earlier this year. I have not yet gotten GOOD at gardening, but I have learned to LOVE it.

A couple of years ago, at the community food pantry and garden in Durham, one of our favorite farmers donated an abundance of tiny, sungold tomatoes. Farmers from the local Farmer’s Market donate extra produce to the Hub every week, so there wasn’t anything special about these tomatoes or the gift from Farmer Liz. It was the end of the growing season, the tomatoes needed to be eaten, and the Hub shares food that needs to be eaten with people who need food to eat.

But, as happens sometimes, we weren’t able to get the tomatoes into the hands of hungry people quick enough, and they got a little too squishy and rotten for us to share in any of our regular food distributions. So, because the Food Hub makes every attempt to be a zero waste operation, that abundance of beautiful, organic sungold tomatoes went into the compost.

The compost operation at the Food Hub is a serious endeavor. Because the garden was sort of an add-on to the original mission of food justice, the compost bins became a very important part of the food cycle. The Hub gets donations from many grocery stores in addition to farmers, we have a constant stream of produce that is just on the far side of fresh, and every week, they feed the compost pounds and pounds of rotting fruit and vegetables.

There’s also all kinds of packaging waste at the Hub, and one of the favorite volunteer activities is shredding cardboard and packaging paper so that all those “greens” in our giant compost bins can be balanced out with plenty of “browns.” Compost is chemistry and biology: carbon and nitrogen work together to break down cellular structures of rotting food stuffs and turn it into beautiful, rich, soil that we use to nourish and nurture new plants back in the garden. We estimated last year that we turned over 2 tons of compost in the last two years. Compost is MAGIC. It is one of the richest images of theological transformation and new life that I’ve ever experienced.

So, the gorgeous sungolds went into the compost. They sat, and cooked, had more produce and shredded paper and fallen leaves and more produce piled on top of them, and volunteers forked them over into a new bin, and the next spring, we shoveled the beautiful, dark brown compost onto all our spring beds in the garden and planted new seeds in them: lettuce and herbs and peppers and squash and cucumbers.

The garden operates on donations, for the most part, and that spring we got some exquisite heirloom tomato plants. We planted the heirloom tomatoes – dozens of them – carefully in the rich brown compost soil, watered and tended them consistently. But none of the heirlooms managed to produce fruit. Rabbits ate the tiny buds, the flowers never turned to tomatoes, and they just did not enjoy growing in our soil.

But the sungold seeds, hidden away in the compost all those many months, LOVED IT.

Before we knew it, sungold tomato sprouts were shooting up in every one of our garden beds. A raised bed full of lettuce got taken over by sungold tomatoes. We tried to weed them out and finally, after weeks and weeks of weeding, just gave up and ceded the lettuce bed over to sungolds.

The herb garden, neatly trimmed and tended, filled to bursting with the largest tomato vines I have ever witnessed, where tiny tomato after tiny tomato budded and grew and ripened faster than we could pick them. Volunteers spent several hot, sweaty Saturdays trying to wrestle the vines into submission. We had so many tiny tomatoes that we decided to send people home with tomato sauce kits – sungolds and herbs from our garden and a little recipe for how to roast and simmer them into homemade sauce.

Tomato sprouts came up in the pepper bed.

Tomato sprouts appeared among the squash vines.

Tomato sprouts filled the cucumber plot.

I weeded out more tomato sprouts than you can imagine over that summer, so many that the tiny little tomato stalks filled my dreams some nights – and they just keep coming.

Even that winter, after everything else in the garden had given up the ghost, after we closed down the beds and planted just a few collard greens and chard to overwinter, NEW tomato seedlings started sprouting up from the fresh layer of compost we laid over those greens.

We had sungold tomatoes coming out our ears, from March until November. None of the fancy heirlooms made a go of it – save one precious roma that I savored – but the sungolds, which WE DIDN’T EVEN PLANT OR MEAN TO GROW – just kept coming.

Seeds, man. They are wily.

//

Jesus’ parables are filled with stories about seeds. In the parable of the mustard seed, which we heard this morning, he talks about a tiny seed that grows into a giant shrub, where birds of the air make their home. The tiniest, most easily overlooked little thing grows into something so sprawling that entire families of birds make their homes in its branches.

Jesus also tells a parable about how someone went out, sowed some seed in the ground and then went home and slept. The seed, Jesus says, sprouts and grows, but the person who sowed it has no idea how it happens. “The earth produces of itself first the stalk, then the head, then the full grain in the head.” And when it is ripe, the person who has no idea how it grew goes out and harvests it.

And Jesus tells this other parable about somebody who sowed seeds in their garden, but while everybody was sleeping, an enemy came and sowed weeds among the good seeds, so that when the plants sprouted, the wheat was choked up with weeds. And the farmworkers, when they see what has happened, go tell the landowner and ask if he wants them to weed out all the weeds. But he says, no, just wait until everything is ready to harvest, and then we’ll get the weeds out and burn them up.

And there’s a parable about a fig tree that just can’t seem to produce any figs. The owner of the tree says to the caretaker, “I’ve been waiting three years for this tree to produce fruit! Let’s cut it down and stop wasting good soil space!” But the caretaker convinces the owner to give it another year, some good fertilizer and see what happens.

Jesus tells parables about farmers, too, like the vineyard owner who hires workers early in the day and then hires more later in the day and ends up paying them all the same day laborer wage no matter how many hours they ended up working.

Jesus is really into gardening parables. And Jesus knows the mystery and magic of seeds. Seeds are wily, and they are powerful.

In her commentary on the parable of the mustard seed, Jewish New Testament scholar (yes, you heard that right, Jewish scholar of the New Testament) Amy-Jill Levine says that for so much of history, we’ve heard this seed parable explained as “something small grows into something bit.” And while that is technically correct, Levine says that it is also…BORING. “To speak of the parable as demonstrating that great outcomes arrive from small beginnings is correct, but it is banal. To note WHAT outcomes might occur provides better provocation,”2 she says.

The mustard seed does grow from “the smallest of all seeds” into “the greatest of all shrubs and puts forth large branches, so that the birds of the air can make nests in its shade.”

The greatest of shrubs! But not just a big tree or bush, mind you, a shrub with big branches where the birds of the air can make nests in its shade. WHAT outcome: that so many creatures are able to make their home.

//

This interpretation from Amy-Jill Levine has really shifted my understanding of that parable and of the very Brethren-y insistence on simplicity and humility. The mustard seed isn’t amazing because it gets big; it’s amazing because of how much care and hospitality it can provide.

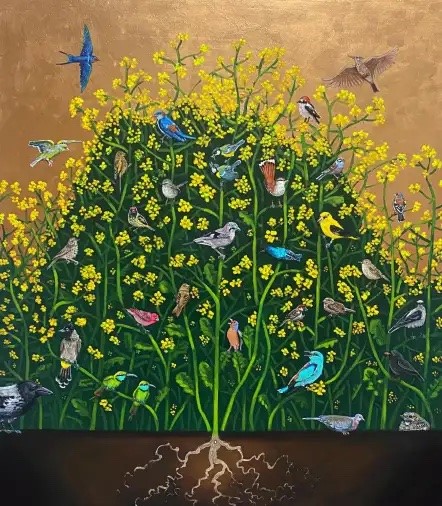

I preached on this parable with my congregation at Peace Covenant before I left there last fall, and I showed this icon by the artist Kelly Lattimore:

Kelly says about this icon:

All of the birds in this icon are native to the Holy Land. Birds in the icon: Palestine Sunbird, Scrub Warbler, Common Rosefinch, Laughing dove, Barn Swallow, House Sparrow, Fire-Fronted Serin, Red- Rumped Swallow, Rufous-tailed Scrub Robin, Woodchat Shrike, European Greenfinch, Tree Pipit, Nubian Nightjar, Northern Wheatear, Green Bee Eater, Eurasian Golden Oriole, European Roller, Eurasian Jay, Great Tit, Hooded Crow, Eurasian Blackbird, Common Chiffchaff, Rock Bunting, Crested Lark, and White Spectacled Bulbul.

The parables, like the sermon on the mount, have always been crucial for the church to imagine the kind of community it is called to be. We discover again and again that Jesus’ parables significance points to everyday life. The parables are meant to be lived.1

With Peace Covenant, I spent some time remembering and naming the many people who found a home with that congregation during my tenure, people who had spent important seasons with us and had since moved away or died or found a new home.

I don’t know this congregation well enough to do that. I’m sure you all could spend a good time remembering and naming people who have found a home here with Washington City CoB over the last decade, or longer.

But I do know that your tiny congregation is being very intentional about opening your doors to people who need a place to be, to light, to rest, to meet. I know that your tiny mustard-seed nature is growing not in the boring, banal, numerical way that Amy-Jill Levine rolls her eyes at but in another, richer, more complicated and interesting way of large branches where anyone who needs one can make their nest.

Aren’t seeds FASCINATING? Yes, small things turn into big ones. But its what those big things DO that’s actually interesting. Seeds blossom and fruit and shed and die and feed the ground again. Seeds burst open and become home for insects and food for birds and nourish the soil beneath them. Seeds grow. Yes. But that growth is not one-dimensional. It’s exponential. It’s in every direction at once. It’s purposeful and beautiful and always in a way that serves the world around it.

Seeds are so wily.

Farmer Liz from Honey Bee Hills ended up selling the farm, buying a sailboat and becoming a USAID contractor. Their delicious, beautiful produce just wasn’t a sustainable way of life for them.

Seeds don’t operate on capitalist timelines. They don’t care about American economics of profit and loss. Seeds are not interested in whether or not their growth can pay the rent or keep staff employed or fill the sanctuary or maintain a business’ financial solvency. Seeds don’t posture or pretend or try to be something they’re not.

Seeds – as Farmer Liz learned – are not a great source of passive income. They are not dependable or consistent, too wily and mysterious and dependent on weather and wildlife and soil quality. Seeds are not a great way to anchor an institution or, most likely, a business.

Seeds are just seeds. They just do what they do, absent any attention to quarterly reports or budget planning or views or algorithms or growth models. Seeds just grow, on their own timeline. We know not how. Sometimes the seeds fail to produce fruit, no matter how attentive or obsessive or consistent their human companions are. But sometimes, when they fall on good ground – which, by the way, we don’t have much control over, either – they produce thirty times what they began with, or sixty times, or one hundred. Seeds are wily.

Seeds don’t care about our human need to control things. They just grow, mysteriously. Sometimes, magnificently. In ways that we don’t understand, in places we didn’t expect, in a manner that somehow, much to our surprise and delight, creates cozy homes for beings who desperately need them. Or gallons of tomatoes for families with empty pantries.

I told Farmer Liz’s husband Rich about the sungolds in the Food Hub Garden. “Well,” he said, “I guess sometimes, you reap what you didn’t sow.”

And there’s a one-liner worthy of a Jesus parable if there ever were one, right?

If God’s kingdom is like a seed – wily, mysterious, unconcerned with our need to force and schedule and understand – what does that mean for how we live our lives of faith? How does it change our spiritual practices? What does it mean for our congregational life? I am curious to hear what you think.