By: Dana Cassell

Luke 5:1-15

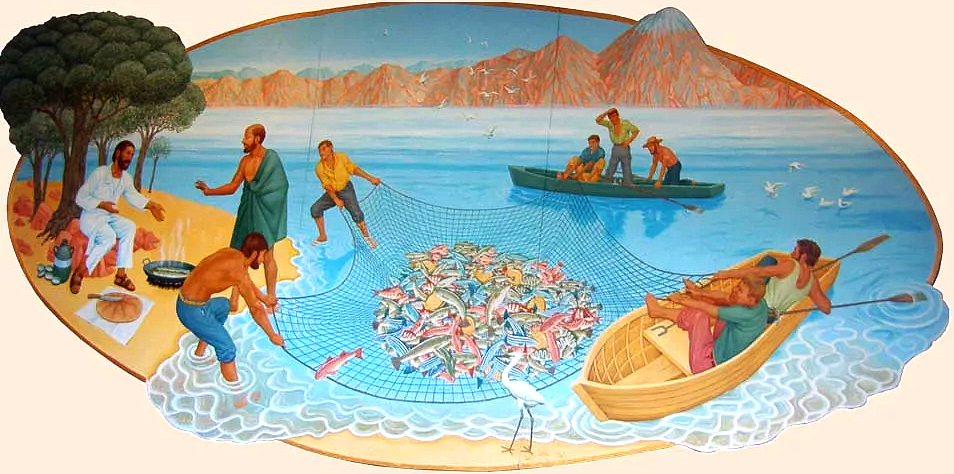

Koenig, Peter. Breakfast on the Beach, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=58541 [retrieved February 12, 2025]. Original source: Peter Winfried (Canisius) Koenig, https://www.pwkoenig.co.uk/

One of my favorite call stories is from Henri Nouwen. It’s not a story from scripture, but a story from very recent history. You might know of Henri, because he was a celebrated Catholic priest, professor, and writer. He wrote a bunch of books on the spiritual life – The Life of the Beloved is my favorite, the one I’d recommend.

Henri spent the majority of his life in school. He studied hard, racked up several degrees, was ordained as a priest and became a professor, working at Notre Dame, Harvard and Yale. By the time this story takes place, in the 1980s, he had become a sought-after speaker and presenter, known around the world for his writing and thinking on both psychology and theology. But in his fifties, something happened that very, very slowly changed the course of his life.

Henri talks about his vocation as hearing two voices – the voice that called him upward, to make something of himself, to be independent and successful, and the voice that called him downward, to stay in touch with his vocation, to stay close to the heart of Jesus. He says that he spent the first half of his life listening to the first voice, becoming successful, pleasing his parents, earning attention and renown and, he says “a lot of tenure.” But he also admits that by the time he was a professor at Yale, teaching and writing and speaking all over the world, he was able to acknowledge a feeling of uneasiness with the direction his life had carried him.

As he tells the story, he came home from teaching one day to his apartment in New Haven to find a woman waiting for him at the door. “Who are you,” he asked her. “I’ve been sent to bring you greetings from L’Arche,” she said. Henri knew that L’Arche was a network of communities where people with disabilities live alongside people without them, sharing life together in intentional ways. “But why are you here?” he asked. “What can I do for you? Can I write something for you? Preach a sermon? Lead a conference? What can I do for you?”

The woman, who had been sent from a community in Mobile Alabama, replied “no, no, I’m just here to bring you greetings. We want you to know that we’ve read your writing and heard about you and I’m just here to bring you greetings.” The woman, Henri says, stayed with him for three days, then went on her way.

And this strange visitor sort of slipped his mind, after she left. He was busy teaching and preaching and writing and speaking, so he mostly forgot that she’d even come by. But several years later, he says, he met the founder of L’Arche, at a silent retreat. They didn’t speak a word to one another, but sat beside one another in a group, praying and meditating together. Finally, as the retreat ended, Henri says, the man said to him, simply: “Henri, I think we might have a place for you at L’Arche. We might be able to provide a home for you.”

And still, Henri continued working and teaching and writing and speaking. He moved from Yale to Harvard, spent time in Latin America studying theology and learning from the church there. More years went by, until Henri realized, at last, that the time of being in the academy was over. “It had been a beautiful time,” he says, but that time was over. And he didn’t know what was next.

But he remembered that visit, and the possibility that L’arche might be a place for him, and so he went to visit one of the L’Arche communities in France. He was partnered with a man named Adam, a young man with severe disabilities, unable to feed or dress himself, unable to communicate very much. But Henri discovered, after weeks of living side by side with Adam, a deep intimacy that he had never before experienced. He began to see the ways that God was at work in Adam, a fully human being, a beloved child of God who served as the person and place where God wanted to dwell. Henri learned to know God in a whole new way.

He spent several months there, and then heard a call to become one of the priests at another L’Arche community in Toronto, which is where he spent the remaining decades of his life.

I’ve heard Henri tell this story at least thirty times – it comes from a video we share at each BVS orientation. I’ve heard it so many times that I can probably quote the entire twenty minute talk from memory. But every single time I listen to the story, every time – even the most recent time, just last week, I am struck, again, by the unexpected power of God’s call in our lives. I am struck, over and over, by how God moves in slow, strange ways, luring us ever deeper into life with him.

That slow rhythm – Henri met the woman from Alabama and then it took YEARS for him to actually meet the founder of L’Arche, then another few YEARS before he heard the call to leave teaching and visit L’Arche – is a part of our scripture for today, too.

//

In the passage from Luke, Simon and James and John have been out fishing all night. They’ve brought their boats to shore, and are washing their nets after a disappointing haul. Jesus shows up on the shore, and – without even a greeting – steps into Simon’s boat. “Take me out a little way from shore,” he says to Simon, who obliges, even though he must have been absolutely exhausted after his fruitless night of fishing.

They row out a little ways, and Jesus sits down and begins teaching the crowds (who, we imagine, gathered once they realized what was happening here, the Teacher commandeering the vessel). When he finishes preaching, he turns again to Simon, and says “put out into the deep water and let your nets down.” Simon protests – he’s been out fishing all night and caught nothing, and now Jesus wants him to go back out into the deep water and put his just-washed nets back into the sea, the sea that he KNOWS is not offering up any fish right now.

“Lord,” he says, “we’ve already tried this spot. Nothing’s biting. I’m tired. I was out all night and then you came over and commandeered my boat and asked me to do you that favor and I did, but this is a little much, asking me to take you on a fool’s mission.”

I imagine that Jesus gave Simon a LOOK when he heard the protests, because there’s no response recorded in the scripture. Jesus LOOKED at him, and Simon probably sighs, gathers up his nets, and rows out farther into the deep. He puts the nets down. And you know what happens – the nets fill so quickly and so heavily that he had to call his fishing partners to bring their boat over. They fill both boats with the fish in the nets, fill them so full that both boats begin to sink with the weight of the abundance.

Simon, who has been yawning and resistant, falls down on his knees before Jesus and repents: “go away from me, Lord, I am a sinful man!”

Jesus refuses to let Simon off the hook, though. This call story is nowhere near finished. This is just the beginning. “Stand up,” Jesus says. “Don’t be afraid. This is just the beginning. From now on, your job will be about this work of abundance not just among fish but among people.”

And – here’s the kicker – Simon and James and John row their sinking boats back to shore, boats loaded down with the most spectacular catch they’ve ever seen, boats they’ve invested their livelihoods in, staked their careers on, fish whose sale could feed their families for months, the nets and ties and oars they’ve used for years – and they leave it all behind. They walk away from all of it. They leave it all, right there on the shore. The trappings of their whole lives, abandoned, forgotten, released in favor of following Jesus, whose call was working on and in them even before he showed up that morning on the beach.

//

I love the dynamic of this story. Jesus doesn’t show up and demand the disciples leave everything and follow him on the spot. He shows up and invites himself in. He shows up and commandeers Simon’s boat. He asks him to row out just a bit from shore, and then he stops. He sits down and preaches a sermon, while Simon waits.

When he’s finished, he asks Simon to row out a little farther, to accompany him for a while longer, to indulge him in this crazy whim even though Simon is clearly exhausted and skeptical. But Simon agrees, and when they get out to the deep water, THEN Jesus asks him to put down the nets again.

And when Simon obeys, when he listens to Jesus and puts down the net, the most amazing thing happens – a miracle. This huge catch is contrary to all reason, logic, science. It is a supernatural occurrence. Simon Peter is convinced. But the story is still not over.

They row back to shore, boats filled with this gift of the giant catch, and then – only then – does Jesus ask them to leave everything and follow him.

//

I’ve been thinking about timelines this week, particularly as I spent a lot of hours on the phone with beloved friends who were being forced to decide whether or not to resign from their federal jobs by midnight on Thursday.

I’ve been thinking about how this false sense of urgency wrecks our nervous systems and our abilities to make good choices. The new administration calls it “shock and awe,” and I’ve seen smart people say that we are being collectively goaded into trauma responses instead of being able to take the time we need to respond from a place of grounded stability.

In scripture, God does sometimes show up and ask people to drop everything to follow Her call immediately, but that’s kind of rare, despite the ways we tell the stories. Biblical characters are usually people who’ve been in conversation with God a long time, who’ve been slowly getting pulled into their roles as prophets, healers or disciples for weeks or months or years before the scene that shows up in the text.

This story about Simon, for example, often gets told as if Jesus was a stranger striding down the shore and demanding use of his boat, but that’s not true. In Luke’s gospel, Simon KNOWS Jesus, and has known him for a while. Jesus has stayed at Simon’s house. He even healed Simon’s mother-in-law of a weird fever. Jesus doesn’t show up out of nowhere and demand immediate obedience – not in this story and, I’d like to say, not ever.

Jesus doesn’t create tight timelines and fake urgency in order to win our subservience. Jesus is not in the business of shock and awe. Instead, Jesus deals in the art of invitation. Hey, can I crash at your house tonight? Can I use your boat for a minute? Would you be willing to row out a little deeper with me? Why don’t you try casting the net another time? And Simon could have, at any of those junctures, said no. He could have refused. And honestly, maybe he already had. Maybe Jesus had shown up the morning before and asked to use his boat and Simon, exhausted from his night on the lake, simply shook his head and apologized, saying he really needed to get home to his family.

If Simon had said no on this particular morning, I am willing to bet that Jesus would not have given up on him. I’m willing to bet that Jesus would have issued another invitation, initiated another conversation, shown up another morning to continue the dialogue, deepen the relationship, patiently come alongside this friend who he wanted to be by his side for all that was to come.

This story of Simon’s call to become a disciple of Jesus is such a great counter-balance to the pace of our political life these days. Real discernment takes the time it takes. Grounded response cannot be rushed. One way we can resist the hostile takeover of our spirits might be to simply refuse to go as fast as the people in power want us to go.

That might look like slowing our work, a time-honored tradition of enslaved people in this country, or throwing sand in the gears of violent processes. It might look like protecting our attention from the onslaught of horrific headlines. It might look like remaining focused on what is ours to do and showing up, steadfastly, where we’ve said we’d be.

Tyrants demand loyalty on their timelines. Jesus patiently invites us to walk together with him. That’s been a helpful reminder for me as the world spins wildly by these last few weeks: it is okay to go slower than you’re being goaded into going. It is good, even, to slow down your reactions in order to offer a carefully considered response. It is a faithful thing to treat others with this same kind of patient respect.